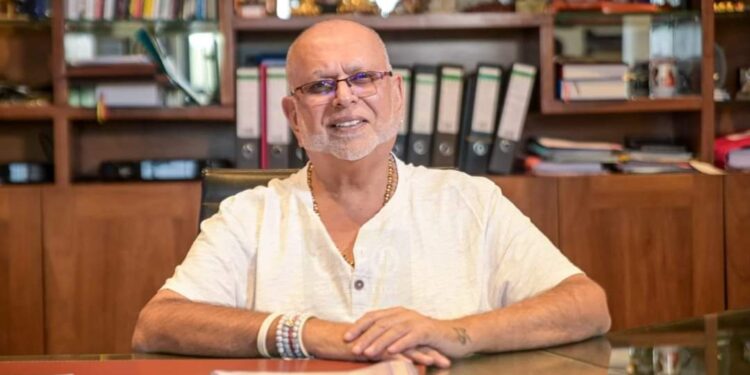

The Supreme Court of Uganda has ordered the Bank of Uganda to pay businessman Sudhir Ruparelia and his company Meera Investments Limited a total of Shs 1 billion in legal costs, marking another major outcome in the long-running Crane Bank case.

A three-judge panel led by Chief Justice Alfonse Owiny Dollo, with Justices Elizabeth Musoke and Stephen Musota, delivered the ruling on October 17, 2025. The decision came after Sudhir and Meera challenged a previous ruling that had drastically reduced their legal cost award from Shs 45.8 billion to Shs 500 million.

In the new judgment, the Supreme Court upheld most of Justice Mike Chibita’s decision but clarified that Sudhir and Meera are separate legal entities, each entitled to Shs 500 million. This brings the total amount payable by the Bank of Uganda to Shs 1 billion.

Chief Justice Owiny Dollo explained that the law does not stop two or more parties represented by the same lawyer from filing separate bills of costs. He said what matters is that any duplicated or unnecessary costs should be disallowed by the taxing officer.

The ruling follows a long legal battle that began in 2016 when the Bank of Uganda placed Crane Bank under receivership over alleged financial irregularities. In 2017, the central bank, acting through Crane Bank, sued Sudhir and Meera Investments, accusing them of misappropriating funds amounting to millions of dollars and billions of shillings, and of taking over 48 properties belonging to the bank without paying for them.

Sudhir and Meera defended themselves and told court that Crane Bank in receivership had no legal capacity to sue. In 2018, the High Court agreed with them and dismissed the case, ordering the Bank of Uganda to pay costs. The Court of Appeal later confirmed that ruling, and in 2021, the Supreme Court again ruled in favor of Sudhir and Meera, ending the main dispute.

After winning the case, the two filed bills of costs claiming over Shs 54 billion each, citing years of legal work and court appearances. The Registrar of the Supreme Court valued the claim at Shs 458 billion and awarded Shs 45.8 billion in legal fees. The Bank of Uganda protested the amount, and Justice Chibita reduced it to Shs 500 million. Sudhir and Meera appealed this decision, arguing that it was too low and did not reflect the scale of the work done.

Chief Justice Owiny Dollo ruled that the case before the Supreme Court was based on a question of law and not on the Shs 458 billion claim mentioned in earlier suits. He said it would be wrong to base instruction fees on that figure because the appeal did not involve a money claim. The Chief Justice added that there was no complexity or new legal issue that could justify such a high award.

He noted that while lawyers deserve fair payment for their work, court fees must remain reasonable so that access to justice is not limited to the wealthy. Justice Musoke agreed with his reasoning, while Justice Musota partly disagreed, saying the applicants deserved a slightly higher award because of the length and difficulty of the litigation.

The court also confirmed that fees for drawings, attendances, and perusals were already covered under instruction fees and could not be charged separately. It maintained that interlocutory application costs should remain at Shs 5 million per application instead of the Shs 50 million earlier awarded.

In the end, the Supreme Court ordered the Bank of Uganda to pay Shs 500 million to Sudhir Ruparelia and another Shs 500 million to Meera Investments Limited. The court reaffirmed that it is the Bank of Uganda, not Crane Bank, that must bear the costs because it was the true party behind the lawsuit.

Chief Justice Owiny Dollo concluded that courts had lifted the corporate veil over Crane Bank and found the Bank of Uganda responsible for initiating and funding the case. The decision closes another chapter in the Crane Bank saga and leaves the Ruparelia Group as the final victor, with the country’s highest court affirming their legal position and awarding them compensation for the long legal fight.

Background

Crane Bank was one of Uganda’s largest and most successful commercial banks until its controversial closure in October 2016 by the Bank of Uganda (BoU). The central bank claimed that Crane Bank was “significantly undercapitalized” and took it over under Section 87(3) of the Financial Institutions Act, placing it under receivership.

However, later investigations, court rulings, and independent audits revealed that the closure was not handled in accordance with the law. The Auditor General’s 2018 report to Parliament found that the Bank of Uganda failed to follow proper procedures when taking over and selling Crane Bank. It noted that BoU could not account for Shs 478 billion it said was used during the receivership process.

Crane Bank, owned by Dr. Sudhir Ruparelia through Meera Investments Limited, had been one of the most profitable banks in the country for years, with over 46 branches and a strong capital base. The takeover was sudden, and within months, BoU sold Crane Bank’s assets to DFCU Bank at what was later described as a “grossly undervalued price.”

When details of the sale became public, they raised questions about conflicts of interest, lack of transparency, and procedural violations. The agreement between BoU and DFCU was made without an open bidding process, and the sale was completed before Crane Bank’s shareholders were given a fair hearing.

In 2017, acting through the defunct Crane Bank (in receivership), the Bank of Uganda sued Sudhir Ruparelia and Meera Investments, accusing them of misappropriating hundreds of billions of shillings and illegally transferring bank properties. But the High Court, led by Justice David Wangutusi, ruled that Crane Bank in receivership had no legal capacity to sue under the law. He concluded that once a bank is under receivership, it ceases to exist as a legal entity capable of filing new cases.

The Court of Appeal and later the Supreme Court both upheld this position, effectively declaring that the Bank of Uganda’s handling of Crane Bank was unlawful. The courts ruled that BoU could not use Crane Bank’s name to file fresh lawsuits, describing the central bank’s actions as an overreach of its legal powers.

These findings confirmed what many financial observers had suspected from the beginning: that Crane Bank was illegally closed, and that the case against Sudhir Ruparelia and Meera Investments was built on a procedurally flawed foundation.

The saga has since become one of Uganda’s most cited examples of regulatory failure and abuse of authority, with Parliament, the Auditor General, and multiple court judgments all pointing to serious irregularities in how the Bank of Uganda managed the takeover and sale of Crane Bank.

For Sudhir Ruparelia and Meera Investments, the successive court victories have vindicated their long-standing position that the closure was unlawful, politically motivated, and economically damaging. The final Supreme Court ruling now stands as a historic confirmation that the Bank of Uganda acted outside the law when it closed Crane Bank and pursued its owners in court.